I’ve watched more of Boots, finishing episode four and just barely starting episode five. The show’s message feels clearer now. My initial curiosity is congealing into grim resignation.

Boots isn’t bad. It’s well crafted. The character portrayals and overt construction of masculinity that piqued my curiosity still remain. I can still enjoy picking through and examining them. I can enjoy stripping them for parts.

The show isn’t bad/wrong, the storytelling isn’t bad/wrong, but I like Boots less now.

Why?

When I last wrote about the show I’d only seen the first episode. I’m glad that I captured my thoughts then. Truffaut’s observations about the difficulty of portraying a critique on the big screen, especially of war or violence, seemed especially applicable as I reflected on that first episode. I thought the show might be trying to go in multiple directions. Many different narrative conclusions were still available, Boots hadn’t yet zeroed in on a single message, and the ambiguity that Truffaut highlighted made all of those potential messages very plausible.

Obviously, *SPOILERS* follow.

After episode four, I’m pretty confident that I know where this show is going. In episode one our protagonist, Cameron Cope, starts off as an outsider who feels like there’s no room for him in the Marine Corps. Hell, he doesn’t even want to be there. He joined with a friend based on a misunderstanding about what was involved.

By the end of episode four, Cope has accepted the challenge of proving that he belongs in the Marine Corps. Moreover, he’s doing that whether or not the Marine Corps wants him (or makes any space for him to exist in it without carving off pieces of himself). In the narrative of Boots, Cope’s act of forcing himself to suffer inside a system that is built to tell him he is unwanted becomes laudable—he’s pushing himself to do something he previously questioned, at considerable danger to himself simply because he’s gay (never mind the literal physical risks), and apparently that’s a good thing. The show loses its critical perspective in the process.

This is a classic propaganda arc. How so? Try this video from Schnee, which is a very worthwhile exploration of the structure of effective propaganda. I posted about it last week. In case you aren’t willing to watch a video right now (even a good one), I’ll give you a summary.

Start with a sympathetic character with sympathetic beliefs. Closely match your sympathetic character and their beliefs to the identity and beliefs of your target audience. Make this character’s choices and actions understandable and laudable for the target audience. Make the audience comfortable in identifying with this character and admiring their beliefs and goals. Make this close alignment between character and audience last as long as you possibly can.

As the story continues, establish that this character has learned (or is learning) even greater truths about the world or themselves that add depth and complexity to the character’s initial beliefs (and thus the target audience’s beliefs) while still being aligned with those beliefs. This character’s discoveries and growth must be portrayed as compatible with their initial beliefs; their growth merely deepens their understanding of their own beliefs (and thus, the target audience’s beliefs). This is aided by shifting your portrayal of the character’s understanding of their dilemmas over time, revealing that what the character originally believed to be simple is complicated, and what the character believed to be complicated is actually simple.

Finally, reveal this deeper understanding with the narrative’s conclusion. Show the sympathetic character making choices that align with their new understanding (choices that serve your propaganda goal) while justifying them with the same values that the target audience has shared all along. Ideally, this whole experience should feel comfortable and rewarding for your audience. You want a feel-good story that reminds people that they too can be good like this character is good.

Schnee’s explanation is superior. I’m just paraphrasing his work. I think the summary is functional enough for my analysis here.

We have our sympathetic protagonist. The young gay man Cameron Cope is stuck in the Marines without really understanding what he’s gotten himself into. He doesn’t want to be a Marine, he doesn’t think he can be a Marine, and he thinks the Marine Corps is a bad place for him to be. He is, however, stubbornly loyal to his friend Ray (the friend who enlisted with him).

We’re also given a cast of characters who don’t necessarily seem like good fits. There’s the fat guy, the (two) stupid guy(s), the Asian-American anxious perfectionist, and the ambitious Black prep kid. There are plenty of others, but these are the ones we have the most access to. In my eyes, these supporting characters are designed to broaden the potential target audience, or broaden the sympathetic cast of characters for our propagandized audience—each is another narrative access point, or person to root for, or both.

Over the first four episodes, Cope displays resolute stubbornness and remains in boot camp. He may slowly come to wish he could be a Marine, but he doesn’t believe that the Marines will accept him. He’s right of course. The Marines wouldn’t accept him if the Corps knew he was gay—heck, his having enlisted and concealed being gay would be considered a crime. He would be punished.

Despite his fear of being charged with the crime of being gay, Cope struggles to stay in so that he can support his friend Ray and the other young men of his training platoon. Cope doesn’t believe he will make it through boot camp, but he wants the others to succeed. Cope’s stubbornness becomes a refusal to let someone else push him out or win at his expense, and his love and support for his friend broadens into a wider sense of camaraderie.

Then, at the end of the fourth episode, the narrative pivots. During a confrontation with his antagonistic covertly gay drill instructor—as the covertly gay DI is wrestling with his own place in the Marines—the DI tells Cope that he can let himself fail, or prove to the Marines that he deserves to be there. This is pretty rich, given that the DI is considering not re-enlisting due to not feeling like he belongs because of his own homosexuality. The scene ends with the DI asking “do you wanna be a marine?” and Cope screaming “YES SIR!”

In this moment Cope’s stubbornness grows into a determination to prove that he really can be a Marine, to prove that he deserves to be in the Corps.

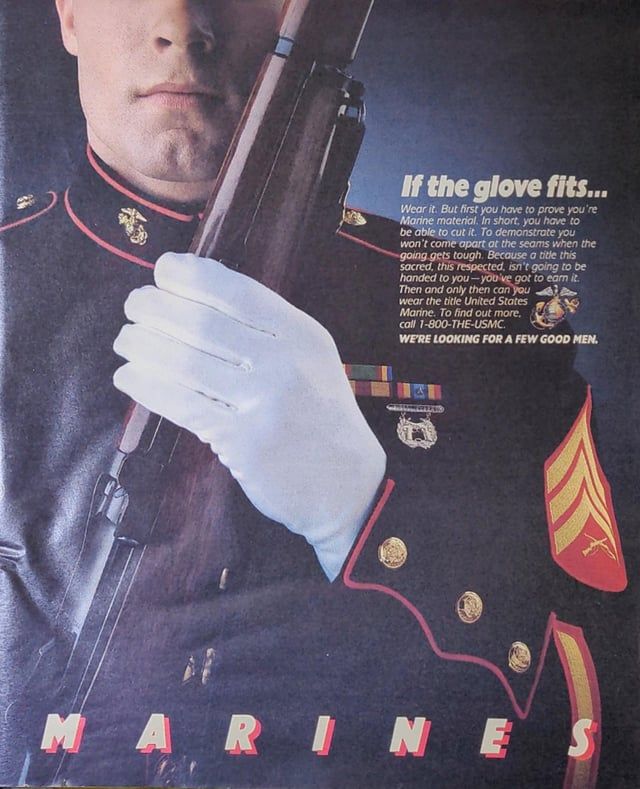

The message I see here is something like: “You don’t belong. You’re not good enough. Does that hurt your feelings? Prove me wrong.” I’ll expand on that; when the Marines say that your existence in the Corps is a crime, or that you have no right to be there, or that you could never make it in the Corps, you should join and serve anyway just to try and prove that you do belong there. It’s a direct challenge, trying to force a choice between accepting the implied insult or standing up for yourself.

It’s pretty hard to create a nuanced or critical depiction of a power structure when you’re telling people they should join that power structure to prove themselves, even if they think joining is a terrible idea—maybe especially if they think joining is a terrible idea. All of the story’s potential critiques are undermined by the story’s overt message. What’s more, with “prove me wrong” there isn’t even a narrative push to change the institution that you’re joining. The fact that the institution hates you is part of the challenge. That stew of hatred and indifference is the point.

This is why I said that the show’s message feels clearer. This is why my initial curiosity has congealed into resignation.

Now, that’s from the end of episode four. There’s obviously still room in the season for a surprise twist. Will that twist happen?

Meh.

First, I doubt it. Second, if the twist does happen, it won’t be a twist that drives Cope off his course of becoming a Marine. Third, I don’t trust the show to deliver a twist that will offer a meaningful critique. The narrative’s trajectory is so clearly established that I’d be shocked to see it successfully land a more critical or complex direction at all.

If the showrunners’ intent was to propagandize, I think they overplayed their hand. They went off too early. They’ve delivered the conclusion of that narrative arc at the end of episode four, about halfway through the series, instead of letting us marinate in Cope’s slow and sympathetic process of change. Is the rest of the season just meant to give us the arduous, glorious story of Cope proving the Marines wrong? Are we supposed to see Cope decide to change the Marines?

I’m not sure it matters. Historically, we know the armed forces didn’t even tacitly accept homosexuality until Don’t Ask Don’t Tell became law years later. So while Cope might prove a point to himself, he’s also going to suffer silently and deny the existence of parts of himself just to serve a Corps that would discard him in a heartbeat. Valorizing that feels… bad.

This show raises many issues, and then doesn’t engage with them. It gives us many narrative opportunities, opens the path to interesting critiques, and then settles on “OORAH!” This is why my curiosity has wilted.

There is still time left in the season for Boots to engage more with the Marines’ (and armed forces’) hostility to homosexuality. I don’t trust it to. There’s time left to engage with the internal costs borne by those who have to carve away and lock up parts of themselves in order to succeed (whether through hiding their homosexuality, or denying that they have anxiety, or whatever). Again, I don’t trust it to.

Here’s another example: Ray, Cope’s friend, struggles with anxiety. He’s the kind of perfectionist who cannot accept failing a task. Ray is given a moment to accept that he might fail. A young female recruit runs into Ray in the doctor’s waiting room and offers wisdom which I’ll paraphrase as ‘you will fail, get used to it, you don’t have to be perfect.’ Ray is obviously enticed (on multiple levels).

That scene feels like the show is reminding us that the show is the cool mom, the one who understands and is chill. But then instead of Ray learning this wisdom, he doubles down into NOT relaxing. It’s not the show telling us that we have to be hardcore to be a Marine, it’s Ray choosing that. Then, Ray’s dad’s unhealthy “lock it up, never let them see it, hyperfixate on the mission” advice is shown to be functional for Ray without further critique.

This normally wouldn’t bother me. It’s an interesting character moment. But it feels exemplary of a larger pattern.

The show positions itself in sympathy with the queer, with the fat, with the stupid, with the anxious… the othered, the ones the Corps doesn’t want. Then Boots shows these recruits enduring (often through unhealthy coping mechanisms) and striving to prove themselves to an uncaring Corps. Sometimes these recruits don’t make it. Then, whether by intent or by the same halo of glamor that Truffaut talks about, Boots celebrates the recruits continuing to sacrifice themselves… and in doing so fails to land a critique.

“Sure,” Boots says, “you could accept that you’ll fail… like a pussy. Or you could BE A MARINE! OORAH!”

So much for being the cool mom. Clearly that was a lie.

In so many ways, my critique of Boots is like my critique of Nimona (the movie, not the comic). That movie promises that queers can be loved if they sacrifice themselves. Boots promises that you too can be accepted if you carve yourself up and stuff what remains into a Marine-shaped box.

I shouldn’t be surprised, really. Carving you up and cramming what remains into a soldier-shaped box is what boot camp, regardless of the branch, is designed to do. I guess I thought that a story about a gay man going through boot camp in 1990 might make a little room for critical examination of that.

I’m pretty sure Boots won’t be that story. Maybe I’m wrong, I’m only halfway through. But I won’t hold my breath.