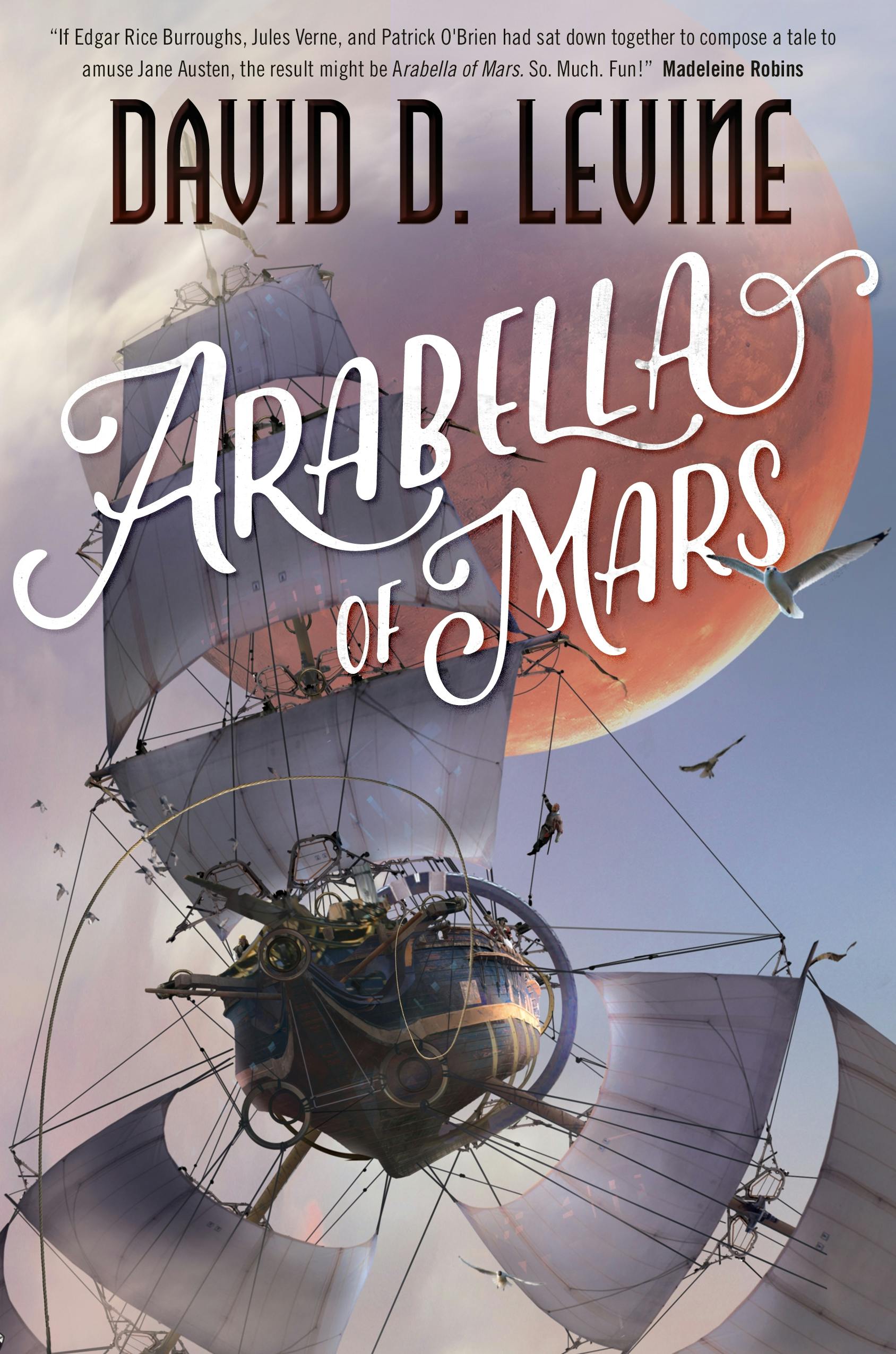

David D. Levine’s Arabella of Mars is an excellent Age of Sail sci-fi adventure story replete with the drama of Regency-era social expectations. It has all the requisite ingredients: imperiled family in need of aid, dangerous shipboard voyages (between planets!), subdued romance, personal rebellion, social maneuvering, and a little bit of marriage. I inhaled this book.

I read perhaps a couple pages on Thursday last week and then spent almost all of Friday devouring the rest of the story. I very wisely did not take the book to bed with me on Thursday night, for which I’m glad. I probably wouldn’t have slept much if I had. As it was, I requested the next two books as soon as I finished on Friday afternoon.

This is the kind of story that I love… and having finished it, I have some concerns. I’ll focus on the things I loved first. Just know that (depending on the course of the next two books in this series) I might have to refile this from “delicious new candy” to “problematic fave“ on account of colonialism.

Also, there are a few things that I’ll cover here which might constitute very mild spoilers. I doubt any of them would surprise someone who’s already familiar with the genres involved, but if you want to avoid spoilers entirely I recommend you skip ahead to the last paragraph.

So. First off, I love the setting.

In the late 1600s, Captain Kidd sailed to Mars. There he explored, met and befriended the bug-like locals, and ultimately sailed back home. There are now human colonies elsewhere in the solar system (including on Mars), and ships which regularly make the voyage from planet to planet across the great rivers of air in between. Clockwork exists and automata are an advanced art, and coal gases are used in great quantities to fill the lift envelopes of airships until they’ve crossed “the falling line”—the elevation high enough for a ship to sail out of a planet’s orbit.

A quibble: I’ve seen this book called steampunk, and I don’t agree. Not yet at least. There are genre similarities, but this story is deeply rooted in the British Regency-era of the Age of Sail. Heck, it’s all set in 1812 or 1813, and the Napoleonic wars are still underway. While certain setting elements overlap with steampunk (clockwork and automata, airships, alternative versions of space) the story has more similarity to Novik’s Temeraire books and other Age of Sail adventures (e.g. C.S. Forester’s Hornblower, or O’Brian’s many naval novels). What’s more, there’s no concern with industrialization or the pressures thereof. So while there’s a little steampunk-ish set dressing, and I can understand using that as a marketing term in 2016 when this book was published, I don’t think it’s accurate.

Back to the setting! Despite the alternate history, social expectations have remained much the same. British Regency Era gender and class conventions are still potent forces, shaping our protagonist Arabella’s world(s). Her taste of something different, what with being raised on Mars by a Martian nanny with very different ideas of gender and class roles, is tantalizing. Levine establishes all of this with admirable efficacy in his quick prologue, setting the stage for the rest of the story and all the conventions that will stymie Arabella in her quest to aid her family.

Actually, I admire Levine’s writing here in general. He’s adopted a markedly period voice, straitlaced and constrained in a way that emphasizes the social restrictions and expectations without sacrificing the feel of personal insight into Arabella’s world. He’s skillful, and it shows. Even when things are predictable (in good, genre-confirming ways) they don’t feel forced.

And, maybe because of all that, this book has lots of fun (mostly quiet) social commentary going for it. Arabella’s struggles and observations around gender and class feel fitting to the genre, and give us a window into Arabella’s growth of her own perspective on what is right, proper, and moral, departing from the ”received perspective” she starts the story with. I really enjoy that growth, and it feels good to see it take place.

But I can’t mention that growth without discussing those concerns I mentioned above.

Stories in the Regency Era, and especially any kind of story involving the creation of colonies in a place with intelligent locals, will unavoidably engage with colonialism. I don’t think it’s possible to avoid in this kind of story, and pretending colonialism (and its problems) doesn’t exist is usually just a way to be an apologist for it. Fortunately, that isn’t the approach this story takes.

Okay, more implicit spoilers ahead, though they should remain pretty general.

For all that Arabella of Mars doesn’t ignore colonialism per se, it also doesn’t address it directly. Partly, I think that’s due to the narrator’s proximity to Arabella’s own perspective; there’s a lot that Arabella hasn’t examined deeply about the social order and her role in it, never mind the ways in which humans and Martians interact. There are, however, many overt hints that Arabella disagrees with or isn’t aligned with the common colonialist assumptions of her society.

This comes out in the little details: Arabella notices the ways in which English depictions of Martians are wrong, and they irk her; Arabella corrects others a number of times, and signals dissatisfaction with their racist and colonialist assumptions; and she is unwilling to embrace the racist and colonialist arguments of others even when they’re not focused on Mars and Martians. As I said, all the little hints are there.

Actually, reflecting on those little details, I wonder whether some of my enjoyment of this story is tied to similarities with how my mother spoke of her childhood in Uganda and the US.

Back to this book, Arabella’s rejection of English colonialism, or her opposition to it, isn’t fully articulated in the way that I think the setting (and the story thus far) calls for. Her own estimations of her fellow landed English gentry start mostly neutral and grow more negative. And she clearly feels more attuned to the social conventions of Martians (or even the crew she serves with) than to the conventions of her peers. But while she appears to judge the existing system as lacking and feels estranged from it, she’s still a part of it and hasn’t articulated a different position.

About par for the course in book one of a series, really. This is part of my reason for both liking the book and trying to reserve judgment.

Anyway. The story thus far feels poised to dive deeper into this struggle with colonialism. And so far, it feels like it’s aware of that. That’s all well and good. But it hasn’t (yet) made that confrontation its focus. If it doesn’t dive into that confrontation with colonialism, or at least face it along its narrative path, I’ll have to revise my opinion of the story.

So.

If you were avoiding reading the spoiler-ish above material, rest assured this is the *END OF SPOILERS*.

I like the book. I like it a lot, and absolutely recommend it to anyone who likes Age of Sail adventure with a splash of Regency drama and a hint of Jules Verne. If you want alternate history science fiction on interplanetary sailing ships, this is your best bet. And if you know a younger reader looking for these sorts of things, this is accessibly YA-ish to boot.

Share this with your friends: