My everyday life is upside down, so please enjoy this soothing picture of Alex the cat.

Category Archives: News

Away, 11/23/23

I’m busy celebrating with family. I hope that you and yours are well, and that you have enough to see yourself through the coming winter. Enjoy food and warmth and light, and may you find peace!

The back-into-it roundup, 11/2/23

There’s a wall that builds itself. It stands between me and my creative work. If I pass through it every day, I can knock it down a little with each trip—moving past it is never effortless, but the wall doesn’t have a chance to grow that much. If I don’t pass through for a while, the wall climbs and solidifies. Pushing past it gets harder the longer I wait.

I shared that image, that metaphor, with Ley when it came to me recently. They nodded, and suggested the metaphor of a quickly-overgrown path that I need to frequently bushwhack and clear. That works for me too.

I’ve been busy doing other work for a week or so. I didn’t think that would be such a distraction from my other writing, but it was. Fortunately, I had the Monuments Men post ready and was almost finished with another World Seed (The Blister is now available for sale!).

But now I’m trying to decide which fiction project to return to, how I want to start bushwhacking—and I’m being pulled in yet another direction by Skip Intro’s Veronica Mars episode for the Copaganda series. Sometimes I watch or listen to interesting analysis (critique and/or appreciation) of stories and find that spark of inspiration. This was one of those times. I don’t know where I’ll take it or what I’ll do with it. Maybe I’ll hunt down more old noir and see if that gives me any new clues.

That’s my ramble for now.

Wait, I should have another review showing up on Geekly Inc soon. I reviewed A Power Unbound, which I enjoyed. I’ll probably have more for you here about that another time, and I’ll let you know when that post has gone live.

Oh, it’s already up! Enjoy.

Traveling

I’m away, spending time with family. I’ll be back next week!

Away with Family!

Not much to see here this week. I’m currently visiting with family, taking advantage of the rare opportunity to see both of my sibs in the same place at the same time, and to spend time with old friends. I hope you’re all having a good week, and I’ll be back again next Thursday.

Mass layoffs, squandered investments

Sometimes there’s a story circulating in the zeitgeist and I have to write about it. Today I’m actually publishing those thoughts instead of shelving them.

There’s a story going around the tech-world (and the people who invest in the tech-world) that laying off staff right now is important, necessary, and a sign of good judgment. It goes hand-in-hand with messages about having over-hired during the pandemic, and messages about an expected recession. I suspect it’s misguided, even if the other connected messages are true and accurate.

Honestly, this current layoff-streak looks to me like companies chasing each other, trying to convince investors that they’re serious and diligent. Better yet, that they’re responsible.

Turns out James Surowiecki sees the same pattern. He has an article on this here. He thinks this looks like a parallel to stories about “downsizing” from decades ago. I see any number of connections to other stories about austerity and responsibility.

I might judge this differently if it seemed like the tech companies involved were firing according to a plan or a consistent basis for judgement. Instead, it looks like they’re firing willy-nilly at all levels. Beyond that Business Insider article, the reports I’ve heard from people working in the affected companies all suggest that this current wave of layoffs is haphazard at best: one reported that the company was still hiring, often for the very positions they just opened by firing experienced workers. It seemed their company paid little attention to the composition of the teams they were firing from, or the relevant experience of the people they fired.

All of that makes me think that this move, firing roughly 6% of a company’s workforce, is more about needing to be seen as doing something rather than about doing the right thing.

So what are the costs incurred by this? If these companies are firing at scale, firing 6% of their employees while still making profit and while still sitting on war chests of as-yet uninvested funds (e.g. Ruth Porat’s segment of Google’s Q4 2022 call)—is that actually a sign of good judgment? Or are these companies shooting themselves in the foot?

In other words, is that story about firing people being the diligent, serious thing to do either true or accurate?

For argument’s sake, I’m going to accept as given that the other two stories are true. I’ll agree that these companies over-hired during the pandemic, and that the economy will either experience a recession this year or at least perform worse than hoped.

I’m not going to dispute any of that.

But what price do these companies pay with these firings? Does it make sense to fire these workers?

Let’s step back. When does it make sense to fire someone?

I posit two general cases:

1) It makes sense to fire someone when they hurt a company more by staying than they do by leaving.

2) It could makes sense to fire someone if their role is no longer relevant to the tasks performed by a company—but that ignores the benefit of reassigning them to a different role and saving on onboarding costs.

I admit, there may be other cases. But I think these two cover the majority of reasonable firing situations.

#2 is probably easiest to understand as a company-wide refocusing of effort. If a company totally shuts down an operation, stops trying to make or support a certain product, etc., it might make sense that some of the staff involved would no longer be relevant to the company’s goals. In that case, firing could make sense.

In counterpoint, I maintain that the company is probably better served by retaining whatever staff it can and assigning them new work in whatever the company’s area of focus may be. Onboarding staff takes time. Training staff takes time. Even if you have to retrain reassigned staff, you’re probably still saving money by conserving your staff pool.

Also, I haven’t seen a dramatic shift in stated plans among the various tech companies that are so eager to fire people. Thus, I don’t think these layoffs fall into case #2.

As for #1… what does it take for an employee to hurt a company more by staying than by leaving?

I’m going to ignore the case of an employee being a toxic piece of shit who harms others around them. That seems like a very clear cut entry in case #1, and it doesn’t match what I’ve heard about the current wave of tech layoffs. If that’s the reason for these firings, they’re firing a lot of the wrong people.

So. How does one calculate the costs of someone staying? How does one calculate the costs of someone leaving?

The costs of keeping an employee can be loosely summed up as “pay, benefits, and overhead.” Employees cost salary or wage, they cost payroll tax, they cost whatever is offered as benefits… there are probably other things I’m missing here: I’m not an expert and this is not intended to be professionally rigorous. But a lot of the costs associated with employee benefits and overhead are reduced by economies of scale: the more X you’re buying, the more efficient that purchase is likely to be. It costs less to offer a ridiculously nice physical work environment for your Nth employee than it does to offer that for your first ten. Based on what I know about negotiating power, etc., I’m willing to bet that those economies of scale remain true to some extent across other realms of company overhead and employee benefits.

Basically, cutting X% of a workforce will reduce a company’s costs. But it will probably reduce those costs by less than X%. Pay isn’t evenly spread around a company’s employees: the C-suite is far more generously compensated than other employees are. And trimming away the costs of benefits offered to that X% likely won’t reduce the total price of those benefits on a 1-to-1 basis, due to the aforementioned economies of scale.

So how much does it cost to fire someone?

In these layoffs, fired employees will receive severance pay. That’s a potentially squishy number, but according to Business Insider, Microsoft expects to pay $1.2 billion in severance for approximately 10,000 employees (averaging $120k per person). If you take Microsoft at their word about their severance package being generous—I’m reluctant to, but this’ll make my math easier—we could guess at a cost of $100k per fired employee.

We can also track how much work-time these companies are losing by firing these employees. What do I mean by that? I mean: there’s a time cost associated with bringing employees up to speed. It’s incurred at the start of any employee’s time at a company. To a lesser extent, it may be re-incurred with any shuffle of personnel.

Friends working in tech tell me it takes roughly six months for someone to be brought up to speed and usefully contribute to a highly specialized team, while ”a quarter or two” might be the normal range for other teams. At the six-month end, firing 6,000 people who’ve been at the company for six months or more is 3,000 wasted worker-years (for reference, Google has fired 12,000 people; Salesforce 7,000; Microsoft 10,000). Even if I assume everyone fired got up to speed in only one month (which isn’t borne out by the spread of teams that lost members), that still comes out to a cost of 500 worker-years for firing 6,000 people. That time was paid for already. Firing those employees, to me, looks like squandering that investment.

What is harder to quantify?

The above math assumes we only count the time of the employee being brought up to speed. It makes no accounting of the time and effort other people on their teams put into helping them catch up. I won’t try to account for that here. Any estimates there would be even more speculative than what I’ve done so far, and I think my assessment of the squandered time investment is already damning.

Another item I can’t quantify here is the cost of the institutional knowledge lost in this firing process. From others’ reporting, some of the people fired have been with their companies for up to 16 years. The company-specific and project-specific knowledge and expertise accrued over a decade-plus of work at a company can’t be understated; knowing who to speak to when seeking answers for specific problems, being able to tell others how older systems work, and having personal experience of previous solutions to prior crises all matter. As with the invested worker-time, all of that is being squandered.

Which brings me to another difficult-to-quantify cost which my friends in tech anticipate: decreased product resiliency. Because “automate yourself out of work” is the standard MO for many development teams, the repercussions of firing chunks of those development teams aren’t likely to be felt until a quarter or two from now when something inevitably breaks. When that happens, it’s a roll of the dice whether the person who designed the system and knew it best is still available within the company. The recent layoff wave, with its apparent scattershot approach, is well-designed to exacerbate those system failures by unpredictably removing the relevant expertise. Maintaining existing products and internal infrastructure will be harder, and that additional load will likely make future development more difficult as well.

All of this is exacerbated by the way in which the firings were carried out, which look a lot like intentional corporate self-harm from the outside.

Those laid off report learning of the firings by surprise. These people were frozen out of their ex-employers’ communication systems with no time given to pass on custody of any of their work to their coworkers. While many of these articles focus on Google, I’ve heard similar reports from people at Athenahealth. Any sane and competent organization—one that wants to preserve continuity of service, continuity of experience, and allow people to pass on custody of their projects to another person without leaving everything in a mysterious mess—would do this differently. Anyone picking up the projects of those who were fired will have to do their best to decrypt whatever notes made sense to the person who thought they’d return to their project the next day. It’s the opposite of good management.

Given that most investors look for companies that take advantage of market downturns to grow their business, this wave of firings seems short-sighted. It appears to have been conducted in a way that guarantees the erosion of product resiliency and handicaps meaningful transfer of projects from those fired to those who remain.

A final element I can’t quantify here: morale.

Companies, whether they like it or not, are communities. Communities function smoothly when their members are able to trust each other and predict each other’s actions. When a company fires 6% of its staff for no apparent reason, that damages any existing trust and puts the lie to predictability. It makes remaining experienced employees more likely to quit, or seek employment elsewhere.

Also, as a reminder, people may be friends with their coworkers. I am not in a position to quantify friendship. I can’t speak to what portion of the people fired had at least X friends, or whether they were real SOBs that everyone was glad to see leave (an ideal candidate for firing case #1). But seeing one’s friends lose their jobs for no apparent reason, seeing them suffer as a result, is disheartening, discouraging, and encourages anger and resentment—none of which are conducive to greater productivity.

Furthermore, I think this article about the pressure recessions exert on union organizing misses a critical point. Tech companies have been trying to quash union formation for years now. When tech companies show they are willing to fire people for no apparent reason, that may discourage and foster fear amongst their employees. But it can also be another incentive for workers to take actions their companies don’t approve of—like organizing. If they might be fired at random despite playing by the rules, what do they have to lose?

Scared people will certainly pay lip service to frightening authorities. But we have about two more years of Biden’s first term left to go. There’s no time in recent history when employees have been more likely to receive federal support in their unionization efforts. If these companies wanted to undercut pro-union sentiment, they chose a strange way to do so.

In summary, I don’t think these layoffs make much sense. The story tech executives are telling, of these layoffs being a sign of their seriousness and diligence and responsibility, simply doesn’t hold water. Even if dramatically reducing costs right now were necessary for these companies, the way in which these companies went through this firing process verges on self-harm.

My reasoning is as follows:

If a company over-hired, and there’s a recession coming, it makes sense to slow down hiring. It makes sense to reduce expenses. If the company were operating on thin margins and had little cash in reserve, that might require drastic measures and targeted cuts.

When a company is still making profit, and is sitting on a war chest of a hundred-billion-plus dollars, it can afford to eat into that reserve in order to conserve its existing expertise and expand its future capabilities.

Instead, Google spent $59 billion on buying back shares (see Ruth Porat’s segment of that Q4 2022 call). That increases stock price. It does nothing to improve a company’s fundamental performance.

Firing a swathe of employees largely at random has considerable costs. It incurs severance pay. It squanders prior investments of time and money. When firing at random, the money it saves in expenses does not match the proportional impact on institutional knowledge and capability. The firings damage worker morale and foster resentment. And the future cost of time lost to fixing broken systems without the people who knew them best, alongside the associated reputational costs when those systems’ failures impact the company’s customers, are injurious.

As far as I can tell, the only way that these firings make sense is if the companies involved expect a dramatic drop in revenue. In a moment of grim comedy, these firings may create the environment for those losses, and make weathering them more difficult.

But this brings me back to my suspicion that these firings weren’t about actual diligence and responsibility. The alternative is that these firings have little to do with the companies’ future performance, and everything to do with signaling to investors.

In response to lower than expected earnings over the last quarter, some investors are pushing for cost-cutting measures. This is fairly normal behavior. Investors who expect a recession are also pushing for companies to prepare, or at least to be ready for slower growth against economic headwinds.

How do companies show that they’re taking these concerns seriously?

By firing lots of staff, by creating a narrative of responsibility and seriousness, these companies are attempting to communicate that they’re sober, clear-headed, business-minded. As with the stock buybacks, this message is a reassurance that the company cares about their investors and will do what it must to improve their stock value. But this privileges short-term behavior over long-term investment.

As someone who owns some shares in some of these companies, this is disheartening. These are bad decisions. They’re bad decisions that have been executed poorly in the most injurious ways. They look to me like a surgeon grinning, hands smeared with blood and full of mostly healthy freshly-excised tissue, reassuring the audience that the cuts they just made were all well thought out. I can only hope the audience is not convinced, and doesn’t reward this behavior.

I have few doubts that these companies will weather our next economic storms mostly intact. They have many billions of dollars in reserve, they can afford to choose poorly again and again. But this? This was a mess.

It’s also an opportunity. Those workers still employed by these companies can make their voices heard. Even if they still believe that the company they work for earnestly shares their best interests, they can organize and push their companies to focus on long-term planning instead of the market-rewarded sugar-high of quick fixes and flashy cuts.

Good luck.

Away

I’m visiting family, and I’ve neglected to prepare a post for today. I am part way through A Taste of Gold and Iron, by Alexandra Rowland, and I’ll probably post about that soon. It’s fun. Court intrigue, gay romance, fun.

I hope that you’re doing well and staying safe and warm. Happy holidays.

Externalities, Perverse Incentives, For-Profit Prisons

I realize, on reflection, that this feels a little John Oliver-y.

It’s something I’ve thought about for a long while. It’s also related to a creative project I’m working on with a friend. Maybe I’ll have more on that here later.

For now, let’s start very zoomed out. Let’s cover some basic questions and concepts before we dive deeper.

Why have a market? What does market competition create that wouldn’t exist if the state provided the service / produced the good instead, without market competition?

Markets—in their idealized and only sometimes achieved form—maximize the efficient production of value within the constraints imposed on them. They reward those companies able to do more, and especially those which do more while spending less. In an ideal market, a company succeeds—winning customers (and thus market-share and greater income) from other companies—by making a better product or service, or offering comparable quality more efficiently than their competitors. Thus, ultimately, success is about maximizing income and minimizing cost.

But companies are only incentivized to minimize the costs they can’t ignore.

This means that, barring external enforcement, no competitor in a market is likely to minimize any cost that can be dismissed as an “externality,” an ignorable cost. For example, prior to the existence of government regulation of pollution, that pollution was an externality (and some pollution still is). So long as there weren’t costs associated with producing toxic ash and soot, few companies bothered to minimize their production of those things.

Those pollutants harmed people working at those companies. They harmed people living nearby, and even people far away. They have poisoned water supplies, killed wildlife, increased the prevalence of disease in humans (and likely caused human deaths). But so long as companies bore no associated costs for these outcomes, they were externalities. Those associated costs didn’t directly harm a company’s profit margin.

This is a pattern. Read about the Tragedy of the Commons, if you want to know more about similar dynamics.

Sometimes those externalities are a direct result of something which produces value for the company. The Cosmos episode “The Clean Room” discusses that to some extent, covering the topic through the history of leaded gasoline.

But sometimes those externalities actually produce additional value for the company, down the line. When this is the case, the company—possibly every company in a given market—is incentivized to create a cost that others must bear because this cost will eventually result in additional value for the company. If this abstraction isn’t clear enough yet, let’s talk about for-profit prisons.

For-profit prisons are paid to house inmates. Generally, they’re paid by the government.

The arguments in favor of for-profit prisons largely revolve around the idea that a for-profit institution will compete in a market, and thereby be incentivized to perform a service more efficiently—i.e. at lower cost to the government & taxpayer—than a non-profit or state-run institution will. For-profit prisons, after all, are strongly incentivized to cut costs wherever and however they can. The benefit of this cost-cutting, the reasoning goes, will be passed on to the taxpayer. Taxpayers will thus pay less for the incarceration of convicts than they would otherwise.

There is a related argument made in favor of for-profit prisons combining this idea of free market efficiency with two other ideas. First, (because of the aforementioned efficiencies, as well as for other reasons) that the free market should provide all goods and services, and second that the government should not compete with companies in the free market. That argument is more ideologically based. It also requires significantly more discussion of how one defines the term “free market.” Thus I’m not going to focus on it at the moment. Right now, I’m just going to talk about incentives and externalities.

For-profit prisons, then, would focus entirely on the service they provide: incarceration. The lives of their inmates after those inmates leave prison would be externalities.

Setting aside those externalities for the moment…

For-profit prisons, like other companies, are incentivized to find additional sources of income available to their business. With prisons, that income could come from the labor of their prisoners, or from charging prisoners for services and goods (phone calls, stationery and writing supplies, stamps, better food, etc.). It could also come from increasing the number of inmates they house. And if they wanted a more reliable level of income (as most companies do), they would be incentivized to ensure that there’s a steady supply of new inmates.

But how could that be done?

In a world where lobbying exists, for-profit prisons are strongly incentivized to pressure lawmakers on multiple fronts. They profit when lawmakers expand the powers of the police and those police secure more convictions. They profit when more behavior is criminalized. They profit when prison sentences are longer. They profit when more people in the criminal-justice system are more likely to be housed in prison.

In short, for-profit prisons benefit when the criminal-justice system treats people harshly.

Let’s bring those externalities, the lives of ex-convicts after leaving prison, back into focus.

For-profit prisons have no incentive to reduce recidivism. They have every reason to want inmates to be returned to prison after they finish their sentence.

When an inmate leaves prison at the end of their sentence, the for-profit prison stops being paid by the government for housing them. The for-profit prison cannot earn money from the ex-convict’s labor, and cannot charge the ex-convict for goods and services. An inmate who leaves the system is lost income. If that inmate eventually returns to prison, that’s more income.

So an inmate’s life-after-prison might not actually be an externality. It might be a resource. Recidivism is good for for-profit prisons. Rehabilitation is bad.

I’ll spell it out. If a for-profit prison did a good job of helping inmates avoid future problems, helped them to find steady jobs and stable housing and healthy social connections, helped them to avoid being charged for another crime after they leave prison—in short, helped convicts rejoin society at large—that would hurt the for-profit prison’s bottom line. In fact, the harder it is for ex-inmates to readjust to society outside of prison—the harder it is for them to avoid being sent back to prison—the better it is for for-profit prisons.

For for-profit prisons, people who are re-incarcerated create additional profit. They’re repeat customers. At best, with these incentives, an intelligently run for-profit prison would be entirely neutral about whether their current inmates successfully reenter society after leaving. Anything less than the most ethical for-profit prison might be reluctant to help ex-convicts rejoin society.

I don’t know about you, but those incentives seem pretty perverse to me.

People in prison are at the mercy of the prison. For-profit prisons may not be omniscient or omnipotent, but they have incredible influence over the lives of their prisoners. And as things stand they have very little reason to make those prisoners’ lives better, or to help those prisoners succeed after they leave.

With the current system, there is every reason for a for-profit prison to house prisoners as efficiently as possible, sell their labor, and charge them for basic goods and services. There is every reason for that same company to create environments that harm convicts’ ability to remain connected with the outside world, or to improve their chances of leading successful lives and remaining unincarcerated after leaving prison. There is every reason for those companies to lobby in favor of making life after prison as difficult as possible—because anyone who is re-incarcerated is just more income.

This means that the government is paying money to companies that benefit from having more people behind bars, and benefit from having those people re-incarcerated after they eventually leave. We’re achieving efficient imprisonment at the cost of incentivizing the incarceration of more people. It’s bad.

See, markets don’t automatically produce the best possible outcome. They encourage companies to efficiently deliver a product within the constraints of the system. They encourage companies to expand their market… and in this case, that means increasing the number of people in prison.

I’ve had to trim back a number of side arguments. I’m not responding to all the possible disagreements I can see with what I’ve written here. Not yet. But fundamentally, I think we have too readily asked “how can we do this through the market?” and failed to ask “should we do this through the market in the first place?”

I can imagine some theoretical way to structure a for-profit prison industry that isn’t incentivized to trap people in a cycle of incarceration, but improving outcomes here would be a whole lot easier if we took the profit-motive out of the equation instead.

Anyway.

You have, to some extent, comics to blame for this brain worm. Maybe I’ll have more on that front for you later.

Back to LARP writing

I’m writing LARP material again!

It’s been a while. I’ve sat on an idea of mine for a little over a year, and I’m finally having the excited conversations with other LARP friends that keep pushing me to develop it. It’s a good feeling.

I’ve also been writing material for a different LARP that my friends are running. This means taking limited information about national histories, and group goals, and maybe a sentence or two about group flavor, and turning that into 400-500 words of group background with coherent flavor. It’s a rewarding exercise, something I haven’t done recently but have plenty of experience with. Plus, it’s wonderful being able to just produce creative work and share it with people immediately.

I’ve stopped doing that here, for a number of reasons, and I regret that sometimes. Maybe I’ll change that again in the future.

As for the fun LARP ideas I’ve been having, they’re tied to a combination of old story ideas I’ve mused over for about five years and a set of scene ideas that have inspired me in the past two years at Wayfinder. The basic concept: PC groups of treasure hunters and historians return to the ancient places of their ancestors in the Shunned Lands to recover lost relics, and in the process discover both why their old stories refer to a prior golden age and why that golden age ended in catastrophe. The rest of the game is all about facing the consequences of releasing the disastrous remnants of that ancient history.

My excited conversations have mostly been about puzzling through how to produce specific scenes, and what we’d need to make them work. It feels really good, engaging with my WFE friends like this outside of the camp season. That collaborative problem solving and supportive creativity is something I always miss during the rest of the year, when I spend most of my time staring at words and trying to cudgel them into some more effective shape.

Perhaps I’ll be able to work more of that into my other writing routines, and carry that excitement forward.

News, LARP writing, Pomodoro

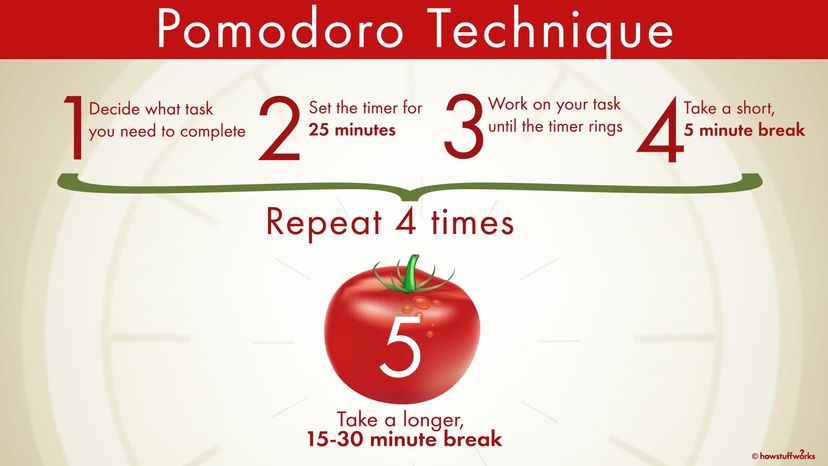

One of my writing group friends suggested I try writing in 30 minute sprints, with a little (also pre-measured) time off between sprints for breaks, other work, other projects. It’s a minimally different variation on the Pomodoro technique. I’m surprised I hadn’t learned this work method before.

I was hesitant to take their suggestion. I usually struggle to fall into the zone that I find so helpful for writing. Writing without being in the zone feels like pulling teeth, getting into the zone takes a while, and… round and round the problem goes. But I’ve been pretty desperate to get more writing done, so I tried it.

It’s fucking phenomenal. I don’t know why it’s working for me right now. And I’m not going to look a gift writing-hack in the mouth.

The other important piece of implementing this for myself has been stricter limits on what I can and can’t do before I start writing in the morning. Listening to music is good, physical movement is good, but reading anything is dangerous, and watching a video is right out (doesn’t seem to matter whether it’s news, documentary, someone’s Let’s Play, or what). I could probably find something that would be okay for me to watch (maybe a sped up painting process for a fantasy landscape), but that would require me to navigate past lots of other enticing videos which would drag my eyes in.

Safer not to risk it. More productive not to risk it.

This is a little awkward, since it means I can’t safely read news before writing. Not even the tech news I use to doublecheck my various sci-fi projects. I also have to avoid responding to any notifications on my phone, which pile up quickly. In fact, this makes it difficult to use my phone at all, even though it’s currently my alarm clock, morning music source, and timer for this approach.

But the upside to this improved morning mental hygiene is that when I set that 30 minute timer I make significantly more progress.

A little context.

I used to regularly produce 2k words a day, mostly without a struggle. Being in that rhythm felt a lot like any other fitness regimen: it hurt to get up to speed, and every so often one of those days would be a total drag. But when I was regularly writing 2k a day, it felt… familiar. Not necessarily comfortable, but certainly not onerous. And at the end of producing that 2k, I felt good. Energized.

Writing with this timer system, with better morning mental hygiene, feels like that. I’m reaching rates close to my 2k a day. It feels great. And when the timer goes off, I can do something else that’s been weighing on my mind before I go back to writing… because I’m free of the need to be writing. I’m not constantly should-ing myself, scolding myself for insufficient focus or insufficient productivity.

I think that’s the biggest lesson I’ve found so far. This external practice frees up my internal judgements. When the timer is on I know it’s time to go. When the timer is off I know it’s okay that I’m not going. That state of being okay with not writing is incredible for my state of mind.

I’ve felt able to let go and make more new stuff that isn’t connected to anything else (yet). That isn’t helpful to my pre-existing projects, but it feels good, like I’m clearing out old pipes that had rusted nearly shut with arterial blockage. Setting aside time like this lets me turn off the voice that’s constantly worrying about what I should be doing right now, what I should be doing next, and just make stuff.

I guess what I’m trying to say is… I’m really appreciating this. I don’t know to what degree this is better brain weather, or better mental hygiene, or a useful way to guide my brain in the right direction. I don’t especially care. I’ll probably try tweaking the lengths of work sprints and breaks, but I’m definitely keeping this.

It’s even helped me feel so much less stuck that I’ve felt free to help friends with material for their LARP. I’m putting together group backgrounds based on a few objectives and a thin thread of preexisting setting, and its rewarding to quickly share those with an appreciative audience. Helps to remind me that I’m competent at this, pulling voice and larger worlds together from a few scraps.