I finished the first season.

Wow.

I know I just wrote about Prodigy last week, but I have to weigh in again.

Continue readingI finished the first season.

Wow.

I know I just wrote about Prodigy last week, but I have to weigh in again.

Continue readingAs someone who grew up on Star Trek: The Next Generation, Star Trek: Prodigy didn’t quite feel like a Star Trek show until episode six. That might be a good thing. As much as I love TNG’s broad focus on an ensemble cast with highly episodic story telling, Prodigy’s early adventure-focused plots with clear continuity from one episode to another gives us a narrative throughline that TNG sometimes lacks.

That narrative throughline and dramatic adventure feels a little like Star Trek: Discovery. Discovery felt a little off to me in its first couple seasons, due to its fixation on a single overarching narrative and its exploration of Michael Burnham’s character to the detriment of the broader ensemble cast. It wore the trappings of Star Trek, but felt more like a Star Trek movie turned into a miniseries instead of a Trek TV show. Unlike Discovery, Prodigy bridges the gap from overarching-narrative to interspersed episodic and big-narrative episodes and makes a smooth landing in that Star Trek sweet spot with episodes six and seven. It starts without the Star Trek trappings, but ultimately feels more Trek to me than the first season of Discovery ever did.

Admittedly, I haven’t yet watched much further (I think I’m on episode twelve of season one). I’m not sure that matters. Even with continued exploration of the slightly-more-main characters, the show would have to veer sharply into main-character-ism to lose what it has already established. I think the tonal shift happened at the right time too. The dramatic narrative of the show’s opening episodes feels right for a space adventure, and the transformation into a Star Trek show happens as the crew finally gels and discovers that—despite their disparate backgrounds and disagreements—they share a moral core that is increasingly influenced by the ideals of Starfleet and the Federation.

That transformation feels deeply satisfying. The crew’s growing recognition of their shared moral core feels deeply satisfying too. There’s something funny about that to me; when I started watching Prodigy I wasn’t sure I’d be able to love the show. The first couple episodes felt so strongly like a kids’ show—without the idealistic themes I love and identify with Star Trek—that I feared I’d be stuck enjoying it on only one level as decent children’s fiction. The show’s growth as it moved beyond the opening episodes proved those fears wrong.

If you appreciate good children’s literature (yes, I’m using that to describe a TV show), or if you love Star Trek, then you should do yourself a favor and watch this show. My friends who recommended it to me were totally right. Prodigy takes a couple episodes to really get into gear, but it’s a delight.

The 5e alignment system is a useful shorthand and a misleading trap. The Outer Planes as presented in the 2014 Player’s Handbook and Dungeon Master’s Guide only make the alignment system’s problems worse. The perfect overlap between alignments and planes—and the total lack of alternative Outer Planes—reinforces the alignment system’s worst inclinations: easy stereotyping, reductionist thinking, and a restriction of creative possibilities.

So what the heck are you supposed to do?

Continue readingSomehow, despite a decade of posts on this blog, I’ve never gone in-depth into Dogs in the Vineyard or what I love so much about it. There’s more to Dogs than I could easily cover in a single post: cooperative story-telling and turn-taking, cinematic descriptive and narrative tools, a conflict mechanic that encourages brinksmanship and escalation, a well-articulated method for understanding what’s at stake… all those elements are a delight.

But there’s another piece that Dogs explicitly encourages groups to home in on. That’s the experience of wrestling with moral conundrums, something many modern CRPGs both want—and struggle—to deliver. That’s what I’m focused on today.

Continue reading

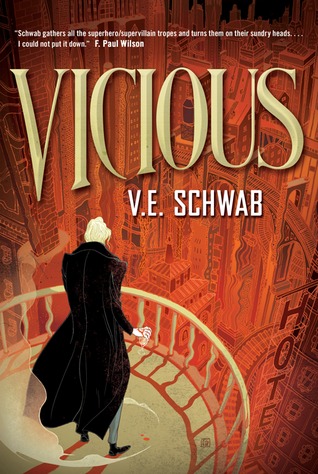

Vicious is a book worth reading. I’d heard that I should read Victoria Schwab’s work, and that I should start here; the first point was abundantly, obviously true, and as to the second… I desperately want more, so it can’t have been that far wrong.

I don’t want to spoil any of the fun for you. But I’ve got to share some of what I loved, because there’s so much here worth admiring.

I admire how Schwab has structured her narrative. She’s done fun things with time, fun things that become obvious at the very beginning when you read the first chapter title: “Last Night.” But what has by now become a trite ploy in TV shows (and all manner of other stories) feels like the right way to tell this story. By the end of the book, it feels inevitable… and that inevitability is itself appropriate.

On top of that, her choices about how to use her narrative voice feel extremely fitting as well. I’ll leave that comment be. I think further discussion of it would risk larger spoilers.

Schwab’s character construction also deserves praise, but to tell you why they’re so wonderful, I have to tell you about Schwab’s writing itself; the joy of reading and knowing these characters owes a great deal to her prose. Often poetic, always evocative, and frequently compelling, her words drip life from the page.

This is a book I feel certain I’ll come back to. I will want to relive it, and I will want to see how Schwab managed to put it all together. There’s so much here to appreciate, so much here to admire. And there’s a great deal here from which to learn.

I strongly recommend reading this book. If your taste is anything like mine, I suspect you’ll devour it whole.