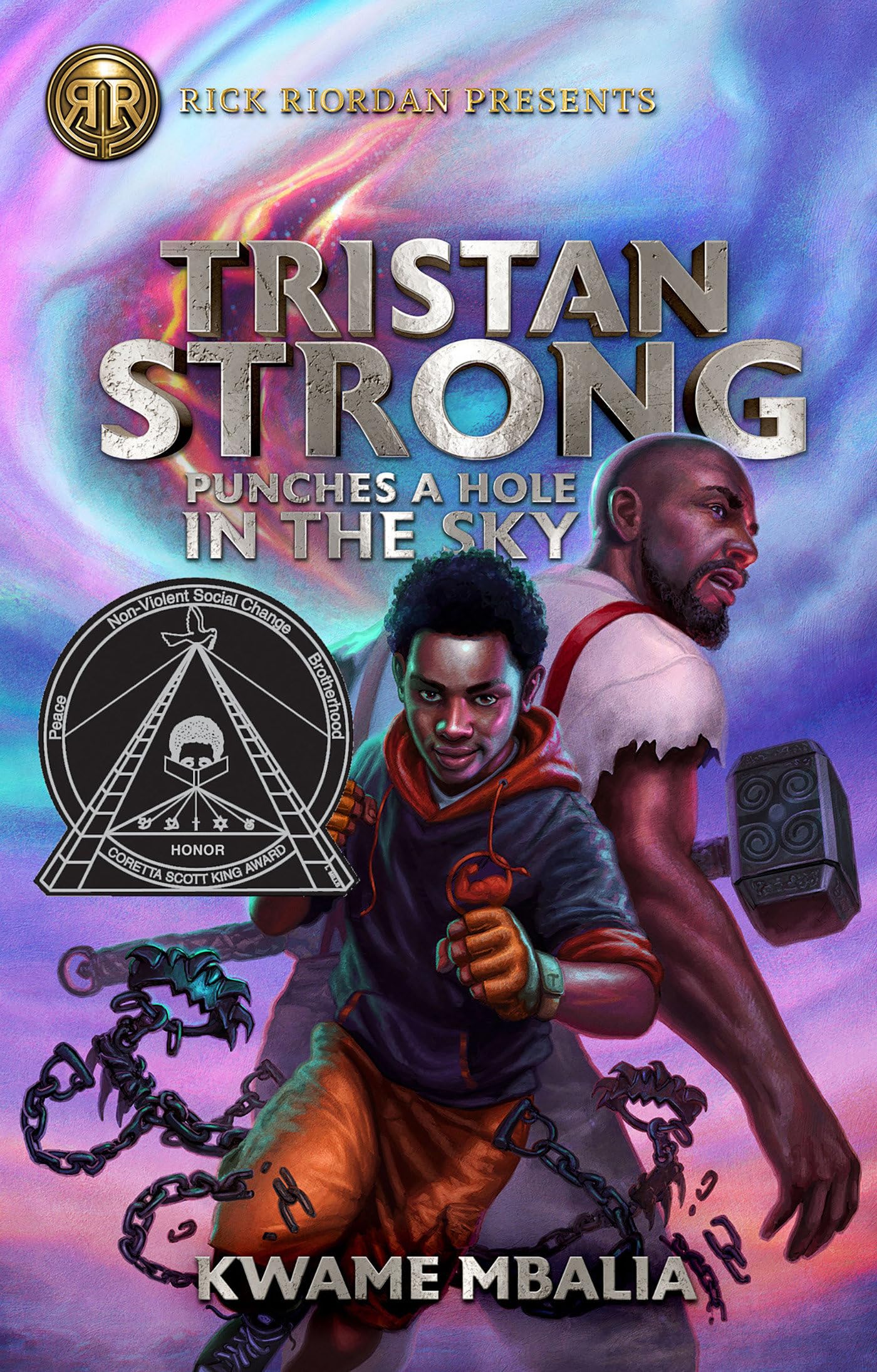

I love a good middle grade adventure story. That’s precisely what this is. As you might expect from something published under Rick Riordan’s imprint, it’s full of mythology and folk tales and legends. Tristan Strong Punches a Hole in the Sky, by Kwame Mbalia, is all about one young boy’s discovery that the stories he’s grown up with (African-American stories with American folk heroes like John Henry, African trickster figures like Anansi, and those who blur the lines like Brer Rabbit) are all far more real than he ever could have believed. It’s fun, it’s pretty fast, it’s (heh) punchy. This is a good book.

I admit, my appreciation for this book is influenced by my desire for more high quality middle grade adventure stories aimed at boys. There’s a lot more to unpack there, some of which can be better understood by reading Of Boys And Men by Richard V Reeves. Read on for some of those details, as well as my few quibbles with Tristan Strong.

Firstly, and maybe my favorite detail: I really like the emotional growth of Tristan over the course of the story. While the plot never really surprised me, the earnestness and honesty of Tristan’s struggles with survivor’s guilt—and the book’s solid advice on how to handle these difficult emotions—were something I don’t remember seeing in a middle grade adventure any time recently. I absolutely loved that part of this book. We need more books aimed at middle grade boys that do this work and wrestle with other difficult topics.

Hold that thought, I’ll come back to it.

The book also has what felt to me like a good voice, with some very weird interruptions. Those interruptions are asides, aimed at the reader, in places and times that I found disorienting. I eventually got used to them, but I never felt like they were being used in a way that added meaningfully to the book—until I reached the very end.

At the end of the book (*very minor SPOILERS*) we learn that this text is a recording, dictated by Tristan (*END SPOILERS*). I actually really like that; I grew up regularly listening to American Indian storytellers, hanging on their every word. The rhythm of the delivery, the occasional interruptions to call on the audience’s attention or make sure people were still listening, that’s all a huge part of the feeling of storytelling within an oral tradition for me. I can feel that in this book. I think that’s what Kwame Mbalia was aiming for, an homage to the oral tradition and its profound importance in the existence of the culture he’s writing from.

I wish that this had landed for me earlier. I wish I’d seen what Mbalia was aiming for earlier, or intuited the connection being made. I would have liked Mbalia to incorporate that a little differently, to make those things happen for me, but… one, I’m not sure how to do it, and two, it’s not my story.

Instead, I’ll just say that this choice almost worked for me the way I think it was intended to. Maybe it will work better for you, or for whomever you recommend this book to.

Now, back to that earlier thought!

I think we have a deficit of good boys’ adventure stories. My emphasis here is on “good.” We have plenty of antiquated boys’ adventure stories—many are pulp fiction, often about adults but written to be accessible to less advanced readers—but those are out of date at best. At worst those old adventure stories are misogynistic, out of touch, and full of old social assumptions that make them better class-discussion fodder than modern entertainment.

Part of this deficit of good boys’ adventure stories is tied to a larger lack; we need more positive visions of masculinity in our stories for kids. We need aspirational visions of masculinity that don’t belittle others, or repeat our old intolerances. These visions of masculinity must connect with kids, offer them a healthy way to be part of the world, and tell them stories that realize their dreams. And, to find traction with readers, these visions must also resonate with some of the other ways in which our society socializes boys.

As a child, I think I found some of this in Star Trek.

Speaking of Star Trek, let’s talk about role models and representation. We’ve known for a long time that it makes a huge difference to see people like yourself out in the world, modeling who and how you can be in the world. While we’ve made significant progress giving girls and young women and (to a lesser extent) genderqueer people roles in our modern fiction aimed at youngsters, I think we’ve forgotten to update the role models for boys and young men. That can’t be the only reason we’ve seen boys’ reading levels falling even as girls’ rise, but I can’t help but think there might be a connection.

Furthermore, as someone who values the advances in equity and equality that feminist activism has achieved, I fear this lack of positive, aspirational representation is sowing the seeds of future backlash. We need male role models (in fiction and in real life) who create and embody a masculinity that uplifts and supports others without lapsing back into old intolerances. If boys are still dreaming of a heroism concocted fifty years out of step with the modern world, we’re all going to suffer from some pretty nasty culture shock.

The key I see here lies in finding positive visions. Yes, I want stories for boys that will help them not harm others, but focusing on that is a negative vision. Negative visions teach people to not do something, to avoid acting. Negative visions might be important and instructive, but they’re paralyzing. We need positive visions. Ending old patterns of misogyny, and queer bashing, etc., has to be a side effect of a positive and aspirational dream to reach for, rather than the side effect of a nightmare to flee.

Tristan Strong feels like it helps.

This book will not—cannot—do it all. It needs to exist alongside many more stories showing other walks of life, other ways to be, other struggles to face. But Tristan Strong is doing its part. The book does so many good things that I’ve simply not written about here because I went off on a tangent and have run out of time. I definitely recommend it and I enjoyed it a lot.

Pingback: First Test, by Tamora Pierce | Fistful of Wits